Oswaldo Cabrera isn’t having the season he aspired to have coming out of Spring Training, which can be said for most players on the Yankees this season. After a fun 2022 season where he belted six home runs and posted a 113 wRC+ in 44 games to help the Yankees win the American League East after it had seemingly begun to slip from their grasp. Entering 2023, hopes were high for the 24-year-old switch-hitting utilityman, with his energetic and infectious personality coupled with a swing that was built for Yankee Stadium, creating the young athletic player the Yankees sorely needed on an aging roster.

Instead, his entire swing path and approach at the plate dramatically shifted, and the hitter Cabrera was to start the year looked nothing like the hitter he was at the Minor League level or Major League level. With a surge as of late, we’re starting to see the necessary corrections for Cabrera to return to form in 2024, but what were those changes, and is he all the way “back”?

A Departure From His Modern Approach

What made Oswaldo Cabrera good wasn’t an excellent raw power tool, great contact rates, or his swing decisions, but rather his propensity to pull the ball in the air. Cabrera slashed .269/.348/.503 last season with 9 HRs in 52 games at the Triple-A level, good for a 124 wRC+, and while it came with a high strikeout rate (25.2%), it also came with plenty of game power. His .234 ISO was well above average, and he did so with a flyball rate of 47.1%, with that number climbing to 50% in his brief Major League stint last year.

The Major League average for pull rate on flyballs in 2022 was 26.4%, and yet Cabrera pulled 43.9% of his flyballs. As a switch-hitter in Yankee Stadium, his spray chart was perfect for a hitter that struggled to reach high exit velocities consistently. A flyball in 2023 has a wOBA of .441 league-wide, which is pretty good, but when pulled? That climbs to .888, roughly double the production of a standard flyball. In 2023, that number dropped to 35.8% for Oswaldo Cabrera, and his flyball rate nosedived from 50% to 39.6%, with his groundball rate climbing from 21.8% to 44.4%.

He cut down on his swinging strike rates from 13.4% to 10.6%, but it came at the cost of the very thing that made him a good hitter. Through his first 184 Plate Appearances, he posted a 43 wRC+ and 20.7% K%, with his groundball rate at 48.1%, it’s clear he cut down on the loft in his swing to try to generate more contact, an approach that made him unplayable at the plate. Over his last 98 PAs, we’ve seen a shift in his approach at the plate that’s focused more on elevating the ball and, as a result, has opened Cabrera up to more sweet spots and better production as a whole.

- The Door Slams Shut: Yankees’ Corey Seager dream hits a roadblock

- Yankees’ Trade or Start Situation: Evaluating Jasson Dominguez’s role in 2026

- The Bidding War: Yankees battling with 2 rivals to sign Michael King

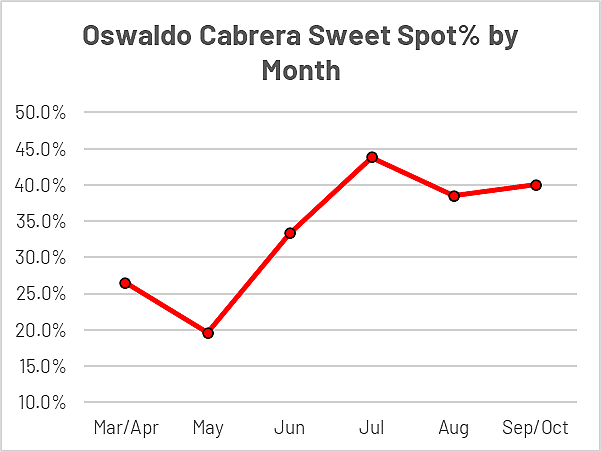

Elevated contact typically means residing in the “happy zone” for launch angles, which Statcast labels as the Sweet Spot, which is defined as a batted ball with a launch angle between 8 and 32 degrees. In 2022, Cabrera had a 41.1% Sweet Spot%, which far exceeds the MLB average of around 33%, but in 2023, that number has plummeted to 28.2%. In July, he seemed to recapture his 2022 profile in terms of launch angles, and since the start of July, he has a 117 wRC+, but the issue still lies in the lack of any power.

He’s only hit one HR in that timespan, and it came against the Pirates in the Yankees’ most recent series, and that has to do with the fact that he’s still struggling to pull the ball in the air, pulling just 26.3% of his flyballs in this timespan, and it’s something the Yankees need to get ahead of in the offseason. It’s clear the swing path that got him his prospect status is still there, and the flare and energy that he’s always had still bursts through in his personality, but the Yankees as an organization have to identify and correct their failures in development this past season.

The Yankees Need to Bridge the Gap in MLB and MiLB Development

For as bad as the Yankees are offensively at the Major League level, they’ve routinely been one of the best organizations in baseball at developing prospects since 2021. From the Florida Complex League to Triple-A, the Yankees are around the league average in terms of roster age for their position players while also ranking in the top half of those respective leagues in OPS, especially the Double-A and Complex League levels, where they had arguably the best team at both levels among the 30 organizations in baseball.

They’ve excelled because of their ability to generate damage contact and make excellent swing decisions, but if they’re doing such a great job at the Minor League level, what’s gone wrong with the Major League team? We know that their philosophy with Dillion Lawson centered around hitting strikes hard, and that took a 2021 team that finished 19th in Runs Scored to a team that finished 2nd in 2022, but if they made such massive strides, why did Jon Heyman report that the Yankees tried to bring Sean Casey in over the winter to become their hitting coach?

Furthermore, how did Joe Migliaccio, who comes from the same school of thought as Dillion Lawson, not only remain the hitting coordinator for the Yankees but also continue to find success with their MiLB development? Well, that’s because the problem wasn’t the teachings, it was the teacher. Back in 2022, the Yankees dropped a crucial Game 2 at Minute Maid Park to the Astros to fall 0-2 in the series, and noted power hitter Giancarlo Stanton came out and said that the Yankees needed to combat the strikeouts and shorten up their swings.

“We’ve got to shorten it up a little it and put the ball in play,’’

-Giancarlo Stanton

How did the Yankees feel? Well, Dillion Lawson flat-out said, “We’re not gonna go in there and develop some new skill…That time has passed. This is about execution.” in response to the quote from Stanton. Disagreement is a healthy and normal part of an organization, and people may think the right approach is Stanton’s, but in this case…Lawson is right. Changing your approach to become a contact-oriented team when you win 99 games by leading the league in HRs is just not sustainable, and it’s certainly not going to fool the Astros much.

Sure, you want to avoid striking out 30 times over the course of two games, but as Lawson alluded to, how is a power-hitting team going to center itself around contact in the middle of the American League Championship Series against the best team in baseball? Well, none of it seemed to matter. The Yankees would lose games three and four at home, get swept, and go quietly into the night, but more importantly, it may be where the seeds of doubt were placed on a “Hit Strikes Hard” mantra that, to the players, seemed to fail them against the Astros.

The Yankees likely didn’t feel as if Dillion Lawson could resonate with the players, and as a result, that’s why they sought out his replacement in the offseason. They didn’t fire Lawson’s people because, quite frankly, they’re brilliant minds who have done a lot of good for the organization. Dillion Lawson himself did a lot of good for the Yankees in 2022, but the rift between him and the players had to have grown large enough that they fired him mid-season, something Brian Cashman doesn’t do.

It’s as if the players on the roster didn’t buy in with the philosophy, but they seemingly misidentified their own issues as well. Giancarlo Stanton, for example, went from having a monstrous .359 wOBA against pitches above 95 MPH in 2021 to a terrible .238 in 2023. His twitch is gone, with Baseball America revealing Stanton to lead all of baseball in average bat speed at 77.2, which seems great on paper, but it’s actually a massive departure from where he was in 2021. Andrew Cresci, now with the Houston Astros (of course), was previously at Driveline, and he revealed in 2021 that Stanton’s Bat Speed sat at 81.3 MPH.

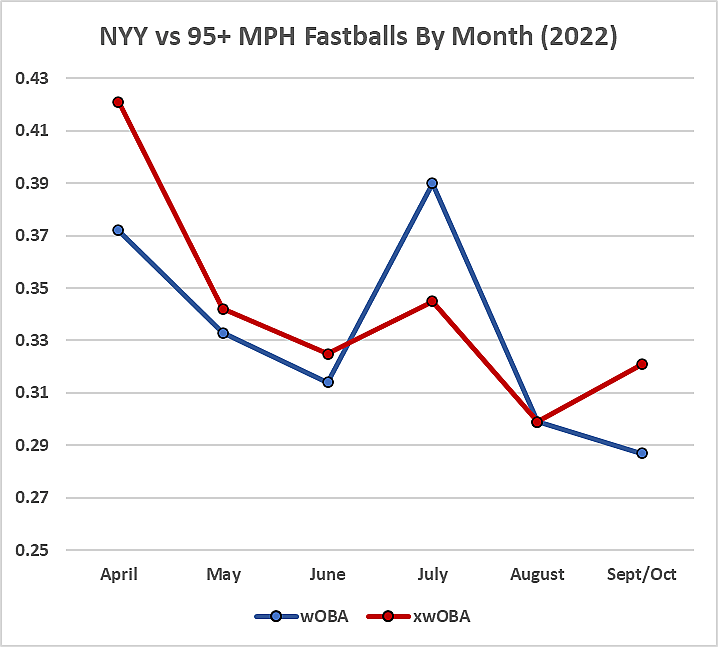

Stanton’s 4.1 MPH decrease in bat speed is likely the largest contributor to his decline, but he identified his postseason struggles in the ALCS as an issue with his power-centric approach; what gives? Well, the Yankees seem to be having this issue on a team-wide basis this season, and it stems from an issue that flared up at the tail-end of 2022.

The Yankees declined significantly in their performance against high velocity as the season carried on, and after being first in wOBA against breaking pitches last season, the Yankees are one of the five worst teams in baseball against that same pitch this season. It makes sense when you realize in 2022, the Yankees had the oldest position player group in baseball with an average age of 30.2, and in 2023, they rolled back an identical lineup, but everybody was a year older with no changes to their offseason routine, but they can look at the West Coast for an example of what they should have done.

The Dodgers sent multiple veterans to Driveline to handle bat speed declines, with some notable drop-offs in performance from formerly reliable bats in Max Muncy and Chris Taylor, but interestingly enough, Mookie Betts also joined the group of Dodgers that went to the facility for bat speed training. For reference, let’s look at their wRC+ and xwOBA in 2022:

- Muncy: 106 wRC+ .339 xwOBA

- Taylor: 93 wRC+ .277 xwOBA

- Betts: 144 wRC+.344 xwOBA

Following months of offseason training for three Dodgers that have already won a World Series and came off of back-to-back 100+ win seasons, they saw their wRC+ and xwOBA numbers improve dramatically:

- Muncy: 121 wRC+, .371 xwOBA

- Taylor: 107 wRC+, .320 xwOBA

- Betts: 171 wRC+, .414 xwOBA

The Dodgers got internal improvement from notable veterans on their team, and that’s why they’re the NL West Champions once again and why they’ll likely go on a deep playoff run in a year where they slashed their budget to reset the Luxury Tax. They’ll likely pursue Shohei Ohtani in the offseason, and they remain a juggernaut in the sport despite the incredible amount of starting pitching injuries they’ve dealt with this season. They identified a league trend of increasing velocity and looked at the data to find a solution: what did the Yankees do?

The Yankees believed their struggles could be sorted out with an old-school approach, as evidenced by the odd changes both Torres and Cabrera made to start the season and the comments made by a leader in their locker room. Both teams have similar financial resources, both teams play in large markets, and both teams have storied histories. In a game where velocity is going up, and teams are throwing more breaking balls than ever before, the Dodgers made the tweaks necessary to handle a brand-new game, but the Yankees didn’t.

Oswaldo Cabrera serves as a perfect analogy for the differences between the Dodgers and Yankees in their directions over the offseason, as while Cabrera’s struggles with high velocity and reaching consistently high exit velocities would have resulted in the Dodgers sending him to Driveline to work on his bat speed, he took it upon himself to make a change that proved detrimental. Had Cabrera taken that year two leap, he could have been 110-115 wRC+ switch-hitting utilityman who could serve as a solution at 3B for a team that doesn’t have an answer there.

With Jasson Dominguez needing Tommy John Surgery, the Yankees could have plugged him in LF and had a stable option there, but now his starting role on the Yankees is completely jeopardized. In 2024, the Yankees are going to need lots of internal improvement from young players and veterans to win the World Series, and hopefully, the Yankees use the case study of Oswaldo Cabrera to go for a more data-driven approach in a game where data continues to expand and improve.

Cabrera has everything in place to be a better hitter in 2024, but the Yankees are going to need to trust the approach that won them the division in 2022 and get the players to trust it once more. It’s not something that requires sweeping changes in the organization, as the Minor League performance serves as the reminder that the infrastructure is all there, and Joe Migliaccio is a young, bright mind with plenty to offer, but it’s a matter of getting that buy-in from their Major League bats.

More about: New York Yankees