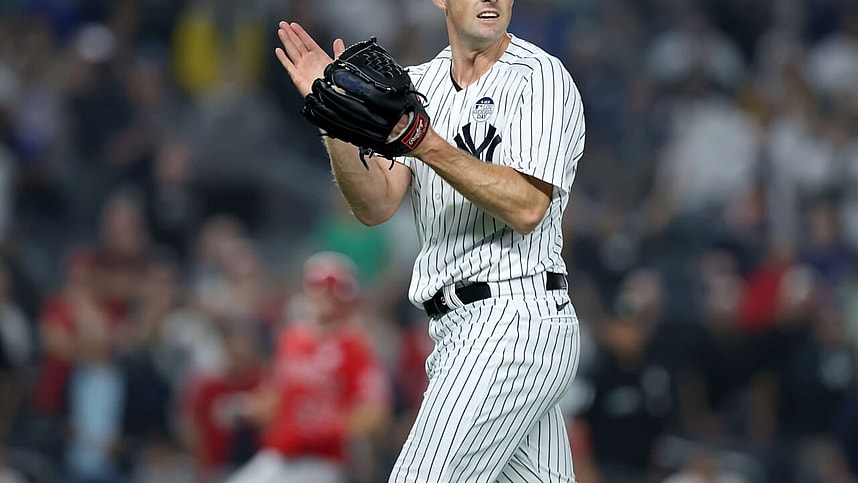

As a notorious jinx, I want to preface this piece by emphasizing that if Clay Holmes allows a run in the outing following this article, my opinion on his changes will not be swayed. The Yankees have had their struggles with trying to figure out how to get Clay Holmes to find success versus left-handed batters, but they may have found a viable option.

A sinker-sweeper pitcher in recent years, the Yankees have caught onto a league-wide trend that shows a lack of effectiveness from right-handers with this arsenal against left-handed opponents, and this tweak to Holmes’ game could result in him returning to his All-Star form.

Riding a current scoreless streak, Holmes is looking to re-establish himself as one of the best relievers in baseball, and I believe that the Yankees have finally found the fix; a second slider.

Clay Holmes and the Duality Of Two Sliders

One of the weirdest phenomenons in baseball is the evolution of the slider, with this pitch category developing two subcategories of the pitch entirely different from one another.

Let’s discuss the gyro slider, a pitch that Clay Holmes threw heavily prior to the 2022 season, which prioritizes vertical drop. A gyro slider utilizes football-like spin with as little spin-induced movement as possible. This is known as gyro spin, thus the term gyro slider, as sliders rely upon the effects, the airflow creates on the seams to generate the downward movement, rather than topspin that generates a downward force in a pitch like a curveball.

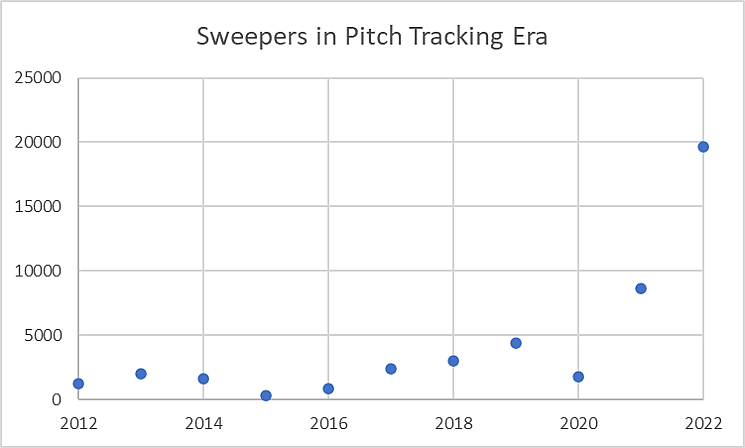

Sweeping sliders (known simply as “sweepers”) prioritize spin-based movement, utilizing a high-spinning pitch with side-spinning action for a big breaking pitch shape, giving it significant horizontal movement. Thrown by getting around the ball, this pitch is one that’s become extremely popular across baseball, with the usage of the pitch skyrocketing in recent years.

The pitch saw a spike in usage in 2021, originally setting the record for the most sweepers used in a season, but 2022 would become the sweeper revolution.

Part of this revolution was Clay Holmes, we discussed wanting to use more of a sweeping slider instead of his more vertical-centric gyro slider, and thus the Clay Holmes we all were enamored with at the start of the 2022 season was born. Unforeseen at the time, but Holmes set himself up for a significant disadvantage against left-handed hitters going forward by completely abandoning the gyro slider.

I want to clarify that adding a sweeper was a great idea, and the results speak for themselves. People point to the fact that Clay Holmes, from July onward, had a 5.33 ERA, but this lacks plenty of context that Holmes was reliable down the stretch and in the postseason.

In 14.2 innings pitched to end the regular season, Holmes had a 3.07 ERA and 2.89 SIERA, posting a positive Win Probability Added, which takes into context the leverage of the situation he pitched in. Include six scoreless postseason innings on top of that, and that’s a 20.2-inning sample size of a 2.21 ERA.

The change he made down the stretch came with the return of his gyro slider, though it was evident the lack of usage on the pitch throughout the season made it inconsistent at times. Nonetheless, he finished 2022 with a .238 wOBA and 45.2% Whiff% on the pitch, and this left plenty of excitement surrounding his 2023 season, the Yankees’ first without longtime closer Aroldis Chapman. So how did things start for the 2022 All-Star? Well, to put it bluntly…not great.

- First 10 Innings

- 6.30 ERA

- 25.0% K%

- 10.4% BB%

- -1.06 WPA

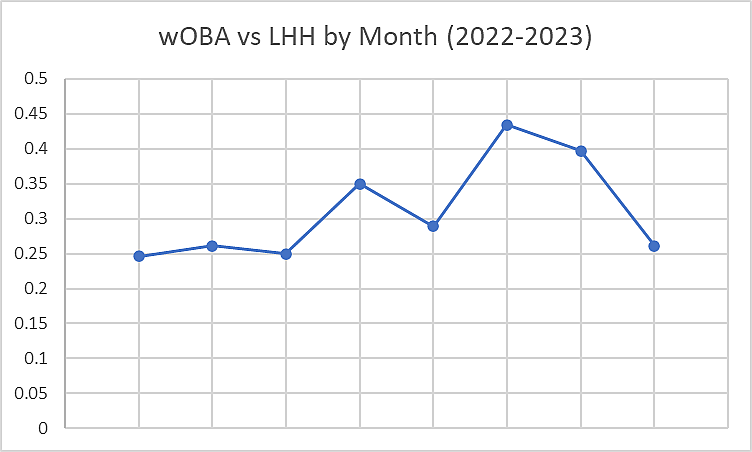

Clay Holmes wasn’t just bad to start the year, he was unplayable against any left-handed batter, making him extremely hard to use in late-game situations where teams can just pinch-hit and stack their lineup with left-handed bats. Opposing teams came full circle on a trend that had become more prevalent as time went on; nothing in Holmes’ arsenal played well to left-handed batters. People will point at command, which indeed did get worse as the season went on in 2022, but his issues against lefties became apparent.

We see a spike in wOBA on point four, representing the month of July for the former Pittsburgh Pirate, as Holmes would go on to post a 7.00 ERA, his worst month of the season. The trend carried into August and September, and this issue was something that the Yankees and Clay Holmes attempted to fix with the gyro slider but didn’t seem to trust the pitch enough to be used as much more than a pitch to change eye levels or throw batters off.

In the postseason, we saw how excellent Holmes could be when he mixed the pitch in well, with lefties registering just a .086 wOBA against because of sequences like the one highlighted by @PitchingNinja on Twitter. Notice who’s at the plate? That’s Jose Ramirez, someone who Clay Holmes was tasked with facing earlier this May, and yet everyone in the ballpark knew Holmes couldn’t get him out. The reason for this is because, for some reason, Holmes still hadn’t bought fully into the idea of mixing in these gyro sliders to left-handed hitters to generate swings down in the strike zone for whiffs.

Against Ramirez, Holmes went with three straight sinkers, with the only one in the zone lined at 101.9 MPH to left field for a line drive single that loaded the bases. To be fair, Ramirez is a perennial MVP candidate who will end up walking into the Hall of Fame, assuming he stays relatively healthy, but this is still poor pitch selection and execution. Let’s cut Holmes some slack, however, as it was a 2-0 count, and going to his sinker to try to get a groundball was a logical choice with the force at all bases except home plate.

Had Jose Ramirez been a right-handed hitter, the gameplan is what it’s been for Holmes ever since he developed his sweeper; either put a patient hitter in a two-strike count to set up chases out of the zone or attack with sweepers away to get an aggressive hitter to bite.

Right-handed hitters tend to struggle more against right-handed pitchers with excellent arm-side or glove-side movement, with horizontal deception playing better than vertical movement. There are exceptions, but for the most part, Holmes’ arsenal plays the same way.

Lefties, on the other hand, experience the inverse effect, and by including a sweeper and removing a gyro slider, Holmes left himself exposed against left-handed hitters. Whereas right-handed hitters have a .334 wOBA and -142.1 Run-Value against sinkers since 2022, left-handed hitters have a whopping .359 wOBA and +106.6 Run-Value against sinkers from RHP. This same phenomenon exists for sweepers, as righties have a .251 wOBA and -93.6 Run-Value against the pitch, and lefties have a .275 wOBA and -0.3 Run-Value.

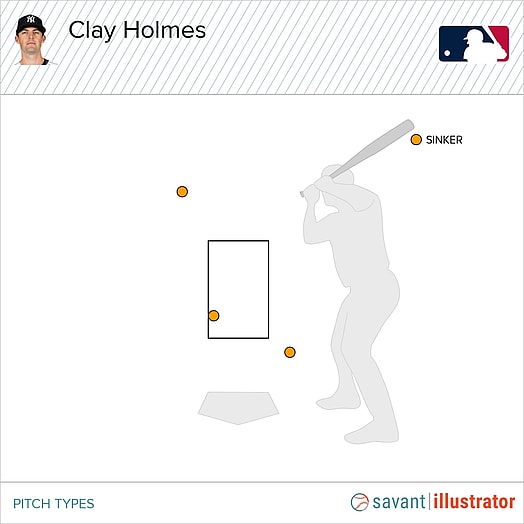

By re-introducing the gyro slider back into his arsenal against left-handed batters, Holmes has re-established a vertical profile that can work versus left-handed hitters. The issue his slider corrected was that Holmes can’t throw a sweeper to a left-handed batter, not throwing a single one all season. In his disastrous start to the season, over 75% of pitches thrown to lefties were fastballs, making him extremely predictable and easy to hit, despite his stuff and command not being too dissimilar to his 2022 season.

In his 9.1 inning scoreless streak, Holmes has brought the gyro slider back in full, using it 36.9% of the time against left-handed hitters and improving the efficiency of his sinker in the meantime. In this stretch, lefties have a .190 wOBA and 42.9% K% against Holmes, who can throw his slider as a legitimate secondary pitch in these matchups and get batters to think. They can’t just sit on his sinker anymore, as he can throw a nasty slider that generates -3.7″ of induced vertical break and just 2.2″ of horizontal sweep.

Why is less sweep important note here? Well, batters also swing less at pitches with larger movement profiles, so by throwing the slider, Clay Holmes is ensuring that left-handed hitters will swing more frequently at his pitches, which leads us to our next concept; the art of generating a swing.

The Yankees Want Batters To Swing Against Clay Holmes

This sounds almost strange; why would you want a batter to go up at the plate and swing when the alternative presents the same floor (strikeout) without the same ceiling of a home run or extra-base hit? Well, this is because of just how uncommon both of those outcomes are relative to walks and strikeouts. For pitchers, they typically see their best results when batters swing more often than not, even if there are exceptions on a case-by-case basis.

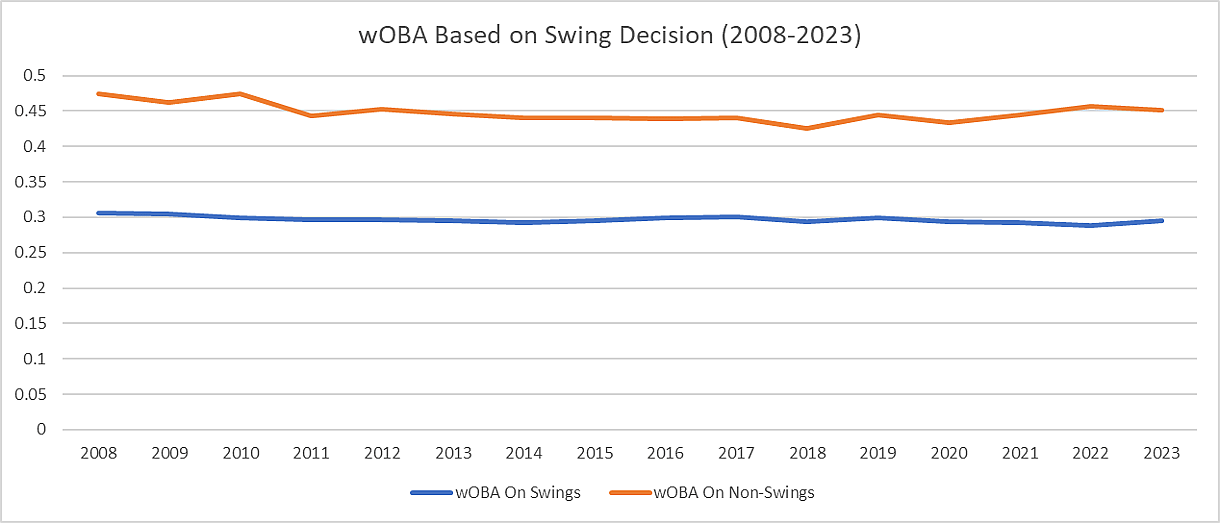

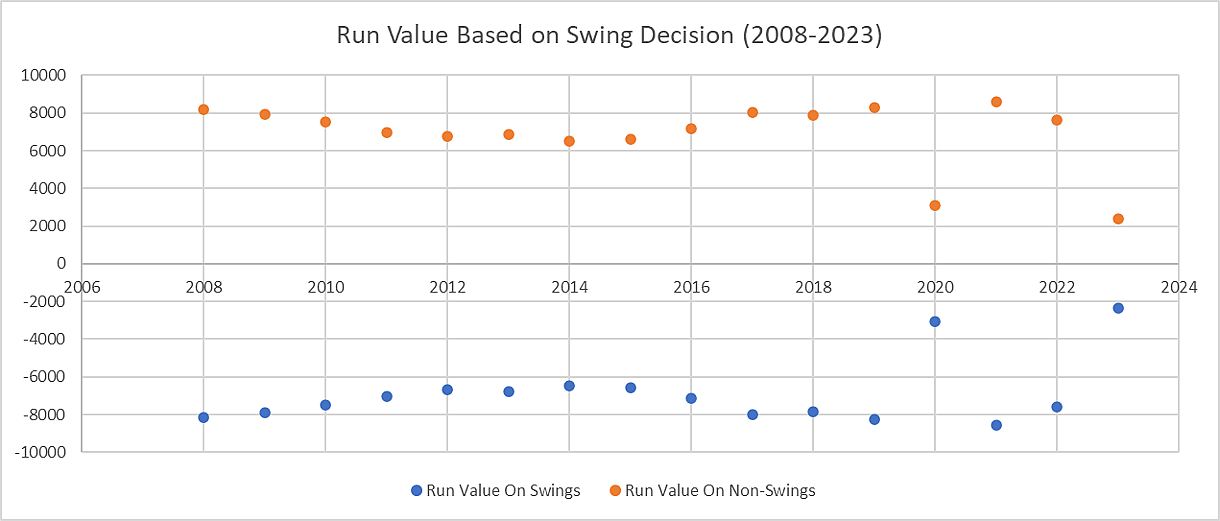

Since Baseball Savant started collecting data on this, we see that not swinging is overwhelmingly more successful for hitters than swinging, but does this take into context the situation a batter swing or doesn’t swing in? Non-Swings are at an advantage since there are only three potential outcomes; strikeout, walk or hit by pitch, whereas swings have a myriad of different outcomes with ranging levels of success. By using a metric like Run Value, we can take into context game situations such as runners on and the number of outs there are to see if this trend holds up.

If you want to have success as a pitcher, get batters to swing! The data in Holmes’ splits with this new slider incorporated into the mix more, as batters aren’t just swinging more at Clay Holmes, they’re chasing way more as well:

- O-Swing%

- First 10 IP: 24.8%

- Last 9.1 IP: 29.4%

- Swing%

- First 10 IP: 39.9%

- Last 9.1 IP: 45.8%

For such a complicated and convoluted discussion about the difference between a gyro slider and a sweeping slider, it really just boils down to how often batters swing against Clay Holmes. The sweeper harmed his swing rates, which is fine because this pitch is absolutely remarkable, and right-handed hitters have a .222 wOBA against the pitch with a 31.3% Whiff%. The issue is that by removing his gyro slider, he took away a legitimate weapon he had against left-handed batters, and when the league made the adjustment of staying patient at the plate and refusing to swing, they realized they could sit on Holmes’ sinker and tee off of it.

The results against left-handed hitters are apparent, and if Holmes can keep this up, he’ll work his way back into the circle of trust once again. His season numbers are rounding back into form as well, with a 3.26 ERA (77 ERA-) and 2.25 FIP (55 FIP-) reflecting his underrated 2023 season. Many people are writing off Clay Holmes, and while a recent shaky outing against the Reds has lowered his stock just a bit, it’s poetic that the team that began the nightmares for Holmes trotted out a left-handed hitter to represent the winning run with the bases loaded in the 9th.

Instead of crumbling in the pressure and losing the strike zone, Holmes would miss with that slider, throw a sinker for a called strike, then go back to the sinker for a routine groundball right back to him, closing out the Yankees’ 29th win of the season and completing a sweep of the Reds. His journey has come full circle, and it might be time to buy stock on Clay Holmes once again.

Skill Interactive Earned Run Average (SIERA): This metric isolates what a pitcher can control, such as strikeouts, walks, and batted ball distribution. For example, a pitcher giving up more groundballs than live drives will generate a lower SIERA since groundballs typically result in more outs.

Win Probability Added (WPA): This metric evaluates how much a player impacts the team’s likelihood of winning a baseball game, taking into account the game situation. For example, Aaron Judge’s game-tying HR has far more significance in terms of WPA than one hit in a game, with the Yankees up seven runs in the 8th inning.

Weighted On-Base Average (wOBA): This metric mirrors On-Base Percentage but takes into account how a runner reaches base instead of just its frequency. It values the event based on projected runs scored, so, for example a home run is better than a triple, a triple better than a double, and a double better than a single.

Run-Value (RV): This metric evaluates the run impact of an event, taking into account the count, runners on, and outs in an inning as well. For example, a swing and a miss on a slider on 0-1 is not going to be as significant as one with two strikes since the former doesn’t result in an out.

More about: New York Yankees