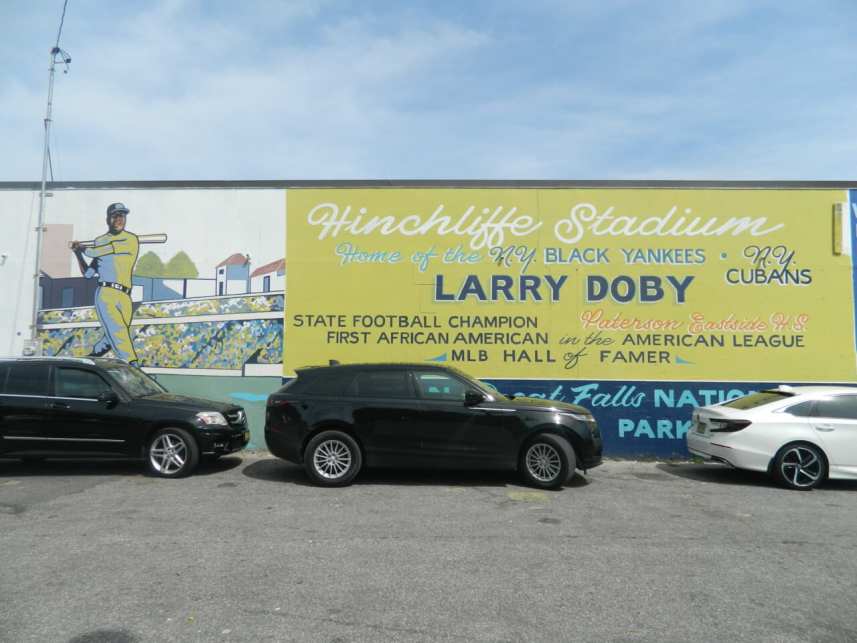

ESM’s look into the legacy of Hinchliffe Stadium and one of its most renowned attractions: MLB trailblazer and Hall of Famer Larry Doby.

For Part I, click here

Major League Baseball is a rare league where second place isn’t guaranteed any form of glory. With five teams from each reaching its postseason bracket, for example, at least one runner-up is guaranteed to be denied entry.

But, in the case of Paterson, New Jersey’s own Larry Doby, his second-place entry held true meaning to the game of baseball and eternally changed the sport, particularly its so-called “Junior Circuit”.

Lawrence Eugene Doby shattered a major baseball color barrier on July 5, 1947. Upon his entry into the Cleveland Indians’ mid-summer tilt against the Chicago White Sox, pinch-hitting for reliever Bryan Stephens, Doby became the first African-American player to partake in an American League game, less than three months after Jackie Robinson made his well-documented debut for Brooklyn. Though Doby struck out in his first plate appearance, it wasn’t long before he was making an impact. The very next day, Doby’s first career MLB hit drove in a run in Cleveland’s 5-1 victory in the latter half of a doubleheader. It would become the first of 1,515 MLB hits over a 13-year career.

But that was far from Doby’s first professional baseball hit, though few were aware of it at the time. Prior to his full-time MLB entry, Doby tallied at least 100 hits as a member of the Newark Eagles, a Negro league staple for 13 seasons, whose statistics were recently ratified as “Major League” tallies by the powers that be in December. Alongside fellow New Jersey resident Monte Irvin, Doby played an integral part of Newark’s triumph in the 1946 Negro World Series, where the Eagles upset the legendary Kansas City Monarchs (headlined by Satchel Paige) in a seven-game set.

Yet, to the naked eye, Doby’s legacy appears somewhat forgotten. While Robinson (rightfully) gets literally an entire day dedicated to his heroics, Doby’s name may be a bit taboo to the casual fan of America’s pastime, even with an invitation to Cooperstown extended in 1998. But make no mistake…those with an intricate knowledge of the game and its integration know of Doby’s vital role.

Doby’s days of baseball stardom, a dominance of athletic events in general, began at Hinchliffe Stadium, starring at Paterson Eastside High School on Maple Street’s diamond, gridiron, and track. Hinchliffe later played a role in netting Doby his first professional opportunities as well. The intersection of Liberty and Maple hosted Doby’s first professional tryout in front of the renowned Manley family, Abe, and future Hall of Famer Effa, who signed Doby to partake in their high-flying Eagles’ endeavors.

In celebration of Doby’s legacy, ESM recently had a chance to sit down with Doby’s son, Larry Jr., to gain his perspective on the ongoing events at Hinchliffe Stadium, as well as his father’s legacy. Doby Jr. has developed a strong career of his own traversing baseball fields across the country, though he’s making different kinds of fireworks in the outfield. The younger Doby has been a staple of Billy Joel’s road crew for over two decades. In 2017, Doby partook in Joel’s first visit to Cleveland, where his father’s number (14) adorns the right upper deck at Progressive Field.

Q: What does the legacy of Hinchliffe Stadium mean to you and your family on a personal level?Â

LDJ:Â On a personal level, my father was never one to speak much of his baseball career. As a young boy, I would always, obviously, want to hear about it. I think anybody would be interested in what their father’s job was, so to speak. Obviously, in what my father did, I was a little bit more interested in hearing the stories. He was never one to talk about that much, but he always, always, always, talked about playing football on Thanksgiving at Hinchliffe Stadium against Central High School.

That was the biggest thing in his athletic career, that’s when he made it. The whole town was there. I don’t know what the numbers were for the games, I’m going to guess it was maybe five-to-ten thousand people. But I guess he felt like the whole city was there watching them, and those are some of his most found memories of his athletics. Those are the ones he shared with me. Therefore, to me, it’s obviously something where I’d sit and I could see in eyes how meaningful (Eastside football) was to him.

Learning the history behind the stadium in general was a great experience too, all the different events that it hosted, what it meant to the city of Paterson, the fact that they had (auto) races there, the fact that they did plays, that Abbot and Costello were there. It’s one of the few remaining stadiums that the Negro Leagues actually played in. It’s just very heartwarming that they see fit to restore it and make it better than it ever was and make it something where some high school kids in Paterson can have some of the fond memories that my dad had. That’s a nice thought and I’m hoping it does actually happen. They’ve been talking about it for a while and it seems that now, through the efforts of many, that it’s going to happen. I’m looking forward to seeing it returned and maybe see it restored to a better condition than it ever was.

Q: How important is it to preserve such a piece of African-American history in this era of reckoning?

LDJ:Â I’m a person who doesn’t believe that they should tear statues down. I feel like it’s history, whether it’s good or bad, and it should be learned and it should be told correctly. As they say, those who do not know history are condemned to repeat it. I would’ve liked those (torn-down) statues to have the real history of what those people represented.

As far as Hinchliffe, whenever you can represent a historical site correctly, I think it’s beneficial. The Negro Leagues to me are a great example of American ingenuity. American ingenuity isn’t only white or Black. (The players) said ‘wow, we’d like to play baseball, show our abilities’. The powers that be didn’t allow them to play with them so they started their own leagues. It floruished for many years and some of the greatest players in the history of the game had their start there. Some of the greatest players in the history of the game played their whole career there and were never able to show their wares on a national site. Therefore, I think it is important and I think it does legitimize and bring attention to the efforts of those people that participated in those leagues.

Q: What’s the best way that people can get involved and educate themselves on this restoration so as to further the cause?

LDJ: That’s a great question, but I don’t know and I wish I had an answer. I know that the mayor is behind this 100 percent and that he’s trying to involve a lot of local businesses and companies in this undertaking. I know my friend Brian LoPinto knows the history backward and forward and might be able to help those who want to get involved. [Author’s note: Brian LoPinto, one of the top voices of the Friends of Hinchliffe Stadium, has been an essential contributor to this project]

Q: What’s the one thing you’d like people to know about the Doby family story?

LDJ:Â It’s basically the same story as Jackie Robinson. It’s not going to get the notoriety or attention because (my father) was number two. I just think it’s so ironic. America is a lot of things. It’s a land of opportunity and a lot of other things. But it’s also a land where it’s so big-hearted and where we give people a second chance. Somebody messes up, people I think love to see people overcome obstacles and rise to the top. The funny thing is that we are so ingrained in giving people second chances but we’re not as fond of the second people to do certain things.

My father happened to be second (in baseball’s integration), so his impact is not known as well and understood. I guess it’s just to say that my father was a humble guy. He never really tooted his own horn. If he wasn’t that kind of person, maybe his story would’ve been known more, but, again, he would always face being number two. The thing that he was proudest of, the thing I’m most proud of, is that because of he and Mr. Robinson’s efforts, little boys were allowed to dream of playing in the big leagues. People came after them. That’s what I would be most proud of, that’s what I would say sums up the kind of person he was. All that stuff started at Hinchliffe. It’s a special place.

Q: What’s the best piece of advice your father bestowed to you?Â

LDJ:Â I guess the best piece of advice he ever said to me was to treat people the way they treat you, and the way you want to be treated. Those are some of his words that still ring true to me this day. We all have natural prejudices. But there’s no room in society for racism. That’s when you say ‘I don’t care who this person is because they’re of this race. I don’t like them, I don’t want to deal with them’. I think treating people the way you would like to be treated and treating them as individuals, I think, is his most important advice to me.

Q: How proud are you of the impact your father has left, particularly on the Paterson, NJ area?

LDJ:Â I’m probably as proud as any son could be of his father. I know that one of the reasons why Paterson holds him in such high esteem was because he never forgot it. Paterson never forgot him, equally. All of his athletics began there, pretty much. He played on integrated teams and had a lot of success. He flourished as an athlete. It was a Negro League umpire (Henry Moore) that had seen him play. That’s the guy that suggested he play in the Negro Leagues. He tried out at Hinchliffe, and the rest, as they say, is history.

He was grateful to his coaches, his teammates, his friends, all the people that supported him in Paterson. I think the legacy is intertwined. He wouldn’t be who he was without this stuff starting in Paterson. In hand, he brings Paterson notoriety because of what he did after he left. It’s a nice love story.

Q: When you look at the state of baseball today, where have you and your family made the largest impact, and what areas need to be improved in terms of being fully welcoming?

LDJ:Â What he’s done is allow people to come after him. Without Jackie Robinson and my father, there’s no Willie Mays, Hank Aaron, Reggie Jackson. Those two guys were the first. It was a great experiment, that what it was called. Can a Black guy play with white teammates? It’s crazy when you think about it today, but then it was a great experiment. They knew that if they didn’t succeed, there might’ve been a long, long time before another person of color was given an opportunity to play Major League Baseball.

The proudest thing about my dad was that, because of him, the door was always open. People came after him. Maybe he didn’t enjoy all the fame and notoriety, but the ones that did are pioneers, sometimes, are not. Their work makes it possible. They don’t get to enjoy the fruits of their labor but that’s what I’m most proud of. After Mr. Robinson and my father, the American pastime was truly All-American.

Geoff Magliocchetti is on Twitter @GeoffJMags